If you haven’t encountered printed electronics yet, you probably will soon. Here’s a short definition of the technology courtesy of Wikipedia: Printed electronics is a set of printing methods used to create electrical devices on various substrates. Printing typically uses common printing equipment or other low-cost equipment suitable for defining patterns on material, such as screen printing, flexography, gravure, offset lithography, and inkjet. Electrically functional electronic or optical inks are deposited on the substrate, creating active or passive devices, such as thin film transistors or resistors.

In its definition of printed electronics, the Wikipedia entry notes that printed electronics is “expected to facilitate widespread, very low-cost, low-performance electronics for applications such as flexible displays, smart labels, decorative and animated posters, and active clothing that do not require high performance.” And though this statement is true, it doesn’t take into account all that’s beginning to happen with the technology.

To get more insight into what’s happening with printed electronics and its potential application in manufacturing, I spoke with Dr. Davor Sutija, CEO of Thinfilm, a Norway-based company focused solely on printed electronics. According to Sutija, Thinfilm is the first company to commercialize printed rewritable memory.

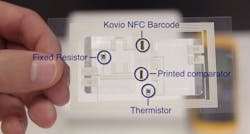

In our discussion, Sutija focused on the Thinfilm’s newest printed electronics product, the Smart Label—a stand-alone, integrated system equipped with memory, sensor, logic, displays, batteries and wireless read technology via near field communication (NFC). The Smart Label’s sensor collects data, sends it via logic to memory and the result is displayed on an electro-chromic display. The data can then be captured wirelessly with a smart device and even sent to cloud-based applications for further analysis.

One industrial example of Smart Label use is to tell the user whether a certain temperature threshold has been exceeded (see video at bottom of this article). It can also be used as a timer label to determine, for example, whether an access badge is valid or not. “Depending on the customers’ needs, we can create different types of integrated systems,” Sutija adds.

Sutija says Thinfilm products are inexpensive to manufacture because of the scalability of its production process. Traditional silicon systems comparable to Thinfilm in function can cost as much as ten times more than Thinfilm, according to Sutija. “The appeal of Thinfilm is its cost-per-function profile. As a result of that lower-cost, scalability benefits,” he says.

“Conventional, silicon-based electronics only scale to the number of people in the world due primarily to cost restraints,” Sutija explains. “So addressing the opportunities introduced by the Internet of Things using traditional methods is not viable. But with printed electronics, due to low cost points and high-volume production processes, we are able to scale to the number of things in the world, not just the number of people. We believe that it will be printed electronics technology and products that power the Internet of Things.”

Clearly the use of printed electronics is still in its earliest stages, but its use is maturing quickly. Most current uses involve bringing electronic functionality into high-volume, cost-sensitive applications, such as in packaging of perishable products, one-time-use medical products, and disposable consumer goods. Thinfilm expect its closed-system Smart Labels with integrated memory, sensors, logic, displays, and batteries to be on the market in 2015. The company plans to provide lead customers with commercial samples of the NFC-enabled version in 2015 as well.

Leaders relevant to this article: