When Intel—one of the largest semiconductor chipmakers in the world—thinks about what it means to have smart technologies and connected machines in manufacturing, the perspective might not meld particularly well with manufacturers in other industries.

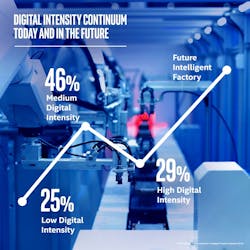

On a spectrum of digital intensity—ranging from primarily manual work all the way up to the intelligent factory powered by Industrial Internet of Things (IIoT) technologies—Intel is positioned far to the right. But it’s important for Intel’s designers to keep in mind that many of its customers’ customers are just beginning to navigate the digital journey.

This is a key reason that Intel undertook a study of Industry 4.0 demands. Its designers and developers are coming from a perspective where the norm is highly automated, closed-loop control with data-driven process tuning. The concern was that the Intel experience might not transfer so well to other industries, which this study confirms.

“It’s making our designers take a step back,” says Irene Petrick, director of business strategy for Intel’s Industrial and Energy Solutions Division. “What if I didn’t have completely automated process control? It’s making us sort of rethink the problem space.”

As Intel makes choices around design options for its IIoT-related products, this study helps the company think about the design in relation to the value it can yield at the end manufacturer, Petrick says. “I can either do what my customers ask me to do, and then my customers would supply those customers, or I can get out ahead of that and understand the problem space that the manufacturers work in,” she adds.

Petrick conducted the study along with Faith McCreary, principal engineer for Intel’s IoT group. They wanted to better understand what workers—from the factory floor to executive suites—expected in factories of the future. “Likewise, we also wanted to uncover pain points, desires, concerns and expectations of these individuals as they and their companies pursue the promise of the intelligent factory,” the authors report. “To answer these questions, we turned to the workers and leaders who are in the midst of today’s changing manufacturing environments.”

Intel recruited 145 participants from a broad range of manufacturing environments. Using a mobile research tool called dscout provided a robust and deep study, supplemented by 11 phone interviews with senior leadership, Petrick says.

A key goal was to try to get a better understanding of the co-evolution of workers and manufacturing operations throughout industry. “When Faith and I looked at this area and said what is an intelligent factory, what will it need to have, how will it operate…we couldn’t find much out there from the human perspective,” Petrick says. There was plenty about communication technologies, bandwidth availability and other technologies needed, but not much about the human factor.

Petrick sees manufacturing leadership struggling in a digital culture—not only with what technology choices to make, but also how to involve workers and engage their interest. “My fondest hope is that this will create a framework to talk about this in a more robust way,” she says.

Although suppliers have come around in recent years—transitioning from a focus on the technology to more discussion of the problems the technology can solve—“that should’ve always been the mantra,” Petrick says. She emphasizes that it’s also important for manufacturing leaders to focus on those pain points if they want to help their workers along the digital journey. “If you have workers on the factory floor who you want to adopt something, it’s so much easier to accelerate the technology by framing it in pain points that it will solve.”

Describing challenges at work, project participants typically focused on pain points rather than technologies. Many of the manufacturing pain points discussed—product rework or damage, physical discomfort or injury, inefficiency or just basic communication breakdowns—could potentially be solved with IIoT solutions, the authors comment.

Workers aren’t averse to Industry 4.0 technologies—but the term itself isn’t well understood. “When you actually talk to participants about what the future might look like, they actually talk about Industry 4.0 types of technologies; they just don’t phrase it that way,” Petrick says. “They want more visibility, they want to know more about their machine status, they want more interaction between their station and other stations, and they identify data silos.”

The study highlights the most frequent types of challenges reported:

- Information challenges (26 percent) related to difficulties getting needed information for work tasks. More specifically, respondents indicated that needed information was not collected, or collected information could not be easily used, or they didn’t trust the quality of the information collected.

- Equipment maintenance and upkeep (24 percent), including unplanned downtime, reactive rather than proactive management, difficulties diagnosing problems, and maintenance costs.

- Communication challenges (19 percent) related to the lack of effective coordination across the factory (e.g. between teams, sites or functions).

- Safety hazards (18 percent) such as environment air quality, temperature, noise levels and ergonomic issues (e.g. lifting heavy objects) top of mind.

- Equipment not a good fit (17 percent) for work, whether the complexity of changeovers, age of equipment, or not using it for intended purpose.

More than half (56 percent) of the obstacles brought up by study participants related to the culture and leadership of the company. When transitioning to a smart factory, it’s common to view leaders as the decision-makers and workers as just being along for the ride. But Petrick and McCreary found in their research that it was not just the manufacturing leaders proclaiming influence, but also operations and logistics coordinators, quality specialists, maintenance technicians and hands-on line workers. Some 56 percent of participating workers and leaders saw themselves as decision-makers at some level about the future of manufacturing at their companies, and almost all of the workers (98 percent) believed that they had direct or indirect influence over technology adoption and implementation decisions.

“These individuals are potential allies in the path to the future, if only we can harness their interest in change,” the authors contend. “Worker participants who embraced technology and coming changes were often motivated by the desire to adapt as a way to stay relevant and employable over the long term. Likewise, they want their factories to change in order to stay in business before they do not have enough capital to adopt new technology.”

Far from the picture that is often painted of the factory worker loath to change, Intel’s study found the opposite. “There’s an actual hunger out there among workers to have better visibility into the work that they’re doing. There’s a hunger for change,” Petrick says. When asked about their best and worst visions of the future, participants’ worst vision was that nothing changed. “We generally describe workers on the factory floor as being afraid of change. That was not found in our study. They anticipate change, they want to participate in it, and they think they should have some say in how it happens.”

As manufacturers make the journey along the digital intensity spectrum toward realizing the smart factory, workers will be expected to transform along with them. To frame this discussion, the Intel study classified workers into three broad categories (or “personas”): hardcore doers, factory influencers and customer champions. In the hardcore doer category, for example, factory supervisors and hands-on workers may shift to the role of factory pit boss, with machines dominating the factory floor; operations coordinators become factory optimizers, with real-time data enabling proactive problem-solving.

“Some positions in the factory will change, but we didn’t see anybody saying humans will go away,” Petrick says. “But they will be much more proactive and driven by data than they are now. The jobs are going from reactive now to much more proactive in the future.”

For more information, read the report brief or the full report, “Industry 4.0 Demands the Co-Evolution of Workers and Manufacturing Operations.”