Manufacturing re-shoring has been turning up quite frequently in the general business press lately. We’ve all heard about Apple’s plan to spend $100 million in 2013 to bring some manufacturing back to the U.S. Then there was The Atlantic article quoting GE’s Jeffrey Immelt as saying outsourcing is becoming “outdated as a business model for GE Appliances.”

As an example of why the model is becoming outdated, The Atlantic article noted that after GE brought back manufacturing of its GeoSpring water heater to the U.S. from a Chinese factory, GE was actually able to reduce the retail price of the water heater from $1,599 to $1,299. Furthermore, this lower priced U.S.-made product was of higher quality and efficiency than the China-produced version.

Of course, several factors figure into this, such as decreases in material and U.S. labor costs, increases in oil prices for shipping, and decreases in natural gas prices for operations, just to name a few. And though I can’t say exactly how much automation plays a role in this example from GE, I’m certain it played no small role. After all, it is largely the increased use of automation that has enabled a great deal of the manufacturing re-shoring that has occurred to date. Even China is increasing its use of robots and other automated devices to offset its own rise in labor costs.

A recent study from IMS Research indicates a shift away from robots being sold primarily for heavy-duty applications such as welding, palletizing and assembly, and toward more lighter duty applications in industries such as food and beverage. The study predicts that the food, beverage and personal care market, along with consumer electronics, will be the two fastest growing sectors for industrial robots from 2011 to 2016.

According to Kiran Patel, an analyst at IMS Research, “Traditionally, work (in the consumer electronics markets) has been carried out by hand in regions of low labor cost, such as China. In recent years, wages have been rising by about 14 percent according to Chinese government statistics. The interest in industrial robots has increased in labor-intensive industries as companies look to automate and cut costs. Taiwanese electronics manufacturer Foxconn has announced that it plans to deploy one million industrial robots in its plants in 2-3 years.”

This increased use of robots in industries like food and beverage has a lot to do with the fact that it is an industry that fluctuates less with changes in general economic activity, says Patel. “With economic uncertainty continuing in the Eurozone, manufacturers of industrial robots do not want all their revenues to come from the automotive industry (which is one of the most sensitive to the rise and fall of the general economy). Manufacturers of robots have reacted by offering robots with a high protection class, making them applicable to food and beverage production,” he adds.

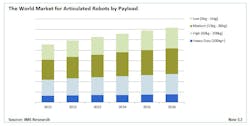

Based on this adaptation, IMS Research predicts that, from 2011 to 2016, revenues from sales of articulated robots with a payload below 15kg will grow by 6 percent a year on average. Investment in automating production of food and beverages and consumer electronics will be the main contributors to this growth. (See chart accompanying this blog).

With the upside of this blog post being that growth in the robotics industries looks promising, the downside is that, as a result, a big uptick in manufacturing jobs as a result of re-shoring may not be in the offing.

So what are the takeaways from all this?

It’s not exactly earth-shaking news but, as I see it, the return of manufacturing to the U.S. will not mean a return of the lower-skill, high-paying industry jobs that flourished for a few decades before and after World War II. In 2011, when Steve Jobs told President Obama those types of jobs weren’t coming back to the U.S., he may not have foreseen Tim Cook’s plan to re-shore some Apple manufacturing to the U.S., but he likely foresaw the continuing decline of low-skilled manufacturing work on a global basis in the face of increasing automation.

Though the outlook for manufacturing employment may not change dramatically as a result of re-shoring, reports like the one from IMS underscore the need for increasing levels of knowledge by those employed in industry. As with the GE water heater example referenced earlier, those results give educated engineers an edge and bolster the case for continuing engineering education.

See Automation World’s Engineering School Innovations for a sample of what some enterprising engineering students have been up to lately.

Leaders relevant to this article: