Hours of boredom punctuated by minutes of sheer terror. That’s how Chris Lyden, senior vice president of business development for the Software and Industrial Automation division of Invensys (www.invensys.com), describes the role of the process operator. “They need absolute clarity of every action they’re supposed to take,” he says.

That human element has become a key deciding factor in whether a process remains safe or becomes a major incident. “The significant effort that has gone into asset reliability over the past two decades has paid off tremendously,” says Eddie Habibi, founder and CEO at PAS (www.pas.com), a company focused on safety. “The area we have overlooked has been the human factor—how that individual impacts process safety. We have repeatedly seen how more accidents are due to human error.”

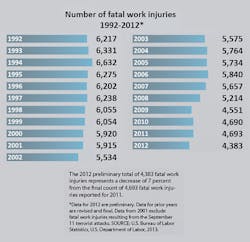

A chart from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics of the fatal work injury rate over the past 10 years indicates that industrial safety has pretty much plateaued after years of improvement. “My guess is that it’s actually getting worse and not better,” says Darius Adamczyk, president and CEO of Honeywell Process Solutions.

Process operators need to remain cool, calm and collected, trusting a control system to guide them through any abnormal situation safely, without stress. That’s not necessarily happening right now, as operators are faced with more to do and fewer people to do it, not to mention increasingly complex and critical systems. “There’s been a tremendous improvement in equipment reliability, but we have overwhelmed the operator with information,” Habibi says.

In continuous process industries, where operations and control are not designed to stop, add to that the pressure of keeping those processes going. “Continuity is paramount,” says Mike Chmilewski, vice president of DCS and safety solutions for Invensys. “Anything you can do to assure continuous operation—safely—the closer you put them to heaven.”

Safety trends

It’s been shown that the biggest indicator that a safety incident is likely to occur is the fact that there have been no incidents recently. “People get lulled into complacence,” says Frank Whitsura, vice president and general manager, process automation solutions, for Honeywell Process Solutions (www.honeywellprocess.com). He calls it small-numbers math: “You can lull yourself into thinking you’re safe.”

The reason for that plateau is not complacence, contends Steve Elliott, Triconex product director for Invensys, but a shift to the human element of the problem. “If you look at industry over 20 years, it’s been focused on occupational safety. It’s made great strides in driving the incident rate down. It’s going in the right direction. Now we’re getting down to the more difficult problems,” he says, acknowledging that the rate is now stalling.

Part of the difficulty is the human psyche—what makes a worker take off his hard hat, for example, when that hard hat is clearly designed to protect him? But in parallel, industry is now looking at process safety incidents, which are not decreasing at anywhere near the same rate that occupational safety has, Elliott says.

Within the category of occupational safety, functional safety is about understanding risks, causes, likelihood, etc., and defining those risks. “You put safeguards in place to manage those risks; they can’t be designed out of the process,” Elliott says. “Therefore you need a layer of management to manage those risks.”

Process safety, on the other hand, is about physically controlling safety to make sure no product escapes from the pipe. The safeguards that get put into place—electrical, mechanical, etc.—need to be regularly tested and maintained. So a valve, for example, will be held open as long as there is never an unsafe condition. The challenge comes in testing the valve, because people don’t want to shut down production, and they also don’t want to put people in danger.

“When you call on the safety system to open or close a valve, you need to know it’s going to happen,” says Jimmy Miller, business development manager for Emerson Process Management’s DeltaV SIS Platform (www.emersonprocessmanagement.com). People typically want to wait for a shutdown, but in an ethylene plant, for example, which takes three to five days to start back up again, that only happens every five to six years.

“People are scared to take the plant down,” notes Keith Bellville, director of modernization solutions and consulting for Emerson. “If you don’t have the right procedures in place, you might bypass some things, and then you’ve just defeated your safety system.”

As a rule, if a system is able to stay productive, it is more likely to be in a safe state. It’s when workers fear a loss in productivity that they will try to bypass safety systems. As John McHale, engineering manager for ABB Jokab Safety, notes, some common misconceptions with safety include that safety systems will impede production and stop people from doing their jobs.

“What we’re seeing now is more performance reporting,” Elliott says. “There’s quite a lot of baselining going on in the industry at the moment—really understanding process safety measurement.” The monitoring and measuring of performance will in turn drive the action piece, he adds. “It’s getting there.”

Safety culture

Because safety relies heavily on human factors, the safety culture of a company or industry can have a significant impact. “There’s a tremendous opportunity to drive better awareness that will facilitate better behavior,” Invensys’ Chmilewski says. “Operators have more on their plates and less time to deal with it.”

Certainly, the intent from manufacturers is to be “more safe,” to ensure they’re exceeding performance objectives, notes Gerry Gutierrez, marketing director for Honeywell Process Solutions. Key factors driving safety behaviors relate to the complexity of chemical processes and operations balanced with the financial and business implications caused by incidents, he adds.

Meanwhile, safety is becoming an increasingly global issue. “It doesn’t matter where an accident occurs, everybody knows about it,” Bellville says, referencing a recent building collapse in Bangladesh that killed more than 1,000 garment workers, exposing abysmal safety conditions in the country’s clothing industry. “Everybody is under the gun to make sure clothing factories are taken care of.”

The energy industry is seeing considerable investment in safety systems as well, according to Emerson. Between oil shale in the U.S. and oil sands in Canada, there’s a huge oil boom in North America. South America is starting to boom now too, Bellville says, and is paying close attention to safety requirements in its aging facilities.

“South American governments are tired of being seen as Third World countries. They want to be seen as taking safety seriously, and governments are starting to see this as a global community,” he says. You can’t do safety to one set of standards in Brazil and another set in Northern California. “You’ve got to put the proper amount of safety and the proper amount of controls.”

Staffing issues

A big challenge with trying to maintain any strong safety culture, however, is a high dependency on contract staff, who bring varying habits with them from other jobs. “It’s very easy to bring a bad habit from another company without even realizing that the habit is not acceptable with the new company,” Elliott says.

This is certainly a common occurrence in the upstream oil industry, Elliott says. Oil sands work in Alberta, for example, “is not exactly an environmentally friendly place,” he says. “People work there for 18-24 months, then move on.”

There have always been contractors; what has changed is the frequency of movement from company to company. It’s a highly competitive marketplace, Elliott says, looking among a shortage of people.

Staffing shortages are an issue throughout industry. “There’s more to deal with and fewer people to deal with it,” Chmilewski says, adding that systems have also become more critical and complex. With increasing regulatory measures and increasing competition in many cases, “the bar is ever-rising.”

Add to this the aging workforce. Nearly 25 percent of the workforce in 2020 will be over the age of 55, preparing to retire, and there will be a loss of key skill sets when this happens. “We still know that operator error is the No. 1 cause of safety issues,” Adamczyk says.

The ASM Consortium points to inadequate operator training as a key factor behind process safety incidents, and notes that 42 percent of process incidents are linked to improper operation or action.

As regulatory measures, competition and staffing demands rise, “the technology needs to rise to the same level or better in order to do the right job for the users,” Chmilewski asserts.

One shift in the technology is gathering information that had been located in disparate sources and bringing it all together to make that information more actionable. “We’re seeing greater connectivity,” Elliott says. “Connectivity will be added into safety systems; not just in the automation system, but also into the business system.”

Consider security and cybersecurity

In the German language, the word sicherheit translates as both “safety” and “security.” Despite German and several other languages relegating it to just one word, they really are distinct ideas—safety considering random faults and failures, and security looking at forbidden influence by intelligent sources.

Nonetheless, suppliers are increasingly emphasizing the point to their process customers that safety and security need to go hand in hand. It is becoming increasingly important that security be brought into any plant safety discussion.

Particularly in less politically stable countries, facilities need to consider potential intrusions. So a decision to take a plant to a safer state should involve both safety and security concerns. Depending on geography, Adamczyk says, “the line between safety and security becomes really small.”

Increasingly, plants need to be concerned about cybersecurity as well. It’s not just the domain of hyper-critical assets, such as when Iran’s nuclear program was targeted by Stuxnet. American businesses have already lost some $400 billion due to cyber attacks, according to Adamczyk. Much of it is just everyday information hacking or employee carelessness.

The key factor tying cybersecurity together with safety has to do with how the two impact the bottom line and therefore need to be treated, says Shawn Gold, global services marketing, performance services, for Honeywell. “Both can have a significant negative impact. You don’t invest in

security or safety to reduce your operating costs either; quite the opposite. They are insurance policies based on known risks that when quantified and assessed properly generate a risk model (actuarial table) that justifies the expenditure (premiums),” he says. “It’s that similarity in treating the premiums as an investment and the need for raised awareness to prevent accidents/cyber events that link the two together.”

Increased connectivity plays a large role in the need for cybersecurity to be part of the safety discussion. “The more that we unify, integrate, connect all these data points together, the more vulnerable we would be,” Elliott says. “An attacker has access to more points into the system.”

Ten years ago, risk assessment related primarily to the physical process. But beginning five or six years ago, the threat was no longer constrained to the plant, and could now come in through various routes like wireless devices, USB ports, etc. “The industry moved toward open standards and the ability to connect various manufacturers’ equipment,” Elliott says. With standardized, off-the-shelf components and Windows-based workstations, companies were able to considerably reduce total cost of ownership of their automation systems. “But we solve one problem and create another,” he says.

With more common failure modes, and integrated control and safety, it becomes necessary to integrate thinking about safety and security, including cybersecurity.

Leaders relevant to this article: